Reclaiming Overlooked Voices in Literature and History

By Darrell Lee

History, as we often encounter it, frequently presents a curated narrative. It spotlights the prominent figures, celebrated movements, and dominant ideologies, inadvertently overshadowing the countless other voices that shaped, challenged, or existed within their complex realities. These marginalized artists, writers, and thinkers, often excluded by accident or design due to their gender, race, class, or unconventional ideas, offer an invaluable counter-narrative. Their contributions are not mere footnotes; they are essential threads in the tapestry of human experience, providing insights into the challenges that define our present moment. Reclaiming these forgotten legacies is not an act of historical revisionism for its own sake but an exercise in achieving a complete and, ultimately, more meaningful understanding of where we stand today. We must actively seek out these narratives, for in their rediscovery, we find not only justice for the past but also clarity for the present.

Art history, for centuries, has primarily centered on the accomplishments of male artists, often relegating their female counterparts to the periphery or erasing their contributions. Such was the case of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c. 1656); she spoke with an urgency that applies to contemporary discussions on gender, power, and representation. Born in Rome, Gentileschi became a Baroque painter, celebrated for her dramatic compositions and powerful female protagonists.

Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi (1614-1620)

Her most famous work, Judith Slaying Holofernes, painted between 1614 and 1620, depicts a visceral scene of female agency and revenge, a theme she returned to multiple times. This intensity undoubtedly stemmed from her own harrowing experience of sexual assault in 1611 and the subsequent public trial in 1612, which subjected her to torture to verify her testimony. Despite her undeniable talent and the patronage she secured from Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and King Charles I of England, her personal history often overshadowed her artistic genius, and she remained largely overlooked by mainstream art historians until the late 20th century. Today, Gentileschi's work stands as a testament to female resilience. Her unflinching portrayal of female strength and suffering compels us to confront questions about justice, trauma, and the representation of women in art and society. Her art, once suppressed, now actively informs our understanding of historical and contemporary feminist struggles.

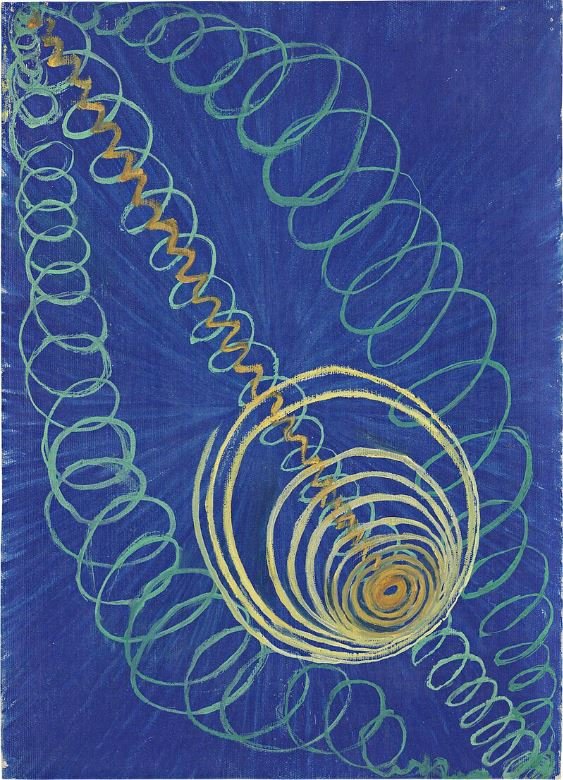

Equally revolutionary, though for different reasons, was the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944). Her monumental series, The Paintings for the Temple, initiated in 1906, comprised over 193 works driven by her spiritual beliefs. Af Klint believed that higher spirits guided her art, and she deliberately chose not to exhibit most of her abstract work during her lifetime. In her will, she stipulated that her abstract paintings should not be shown until 20 years after her death, as she was convinced the world was not yet ready to understand them.

Primordial Chaos (1906–07) by Hilma af Klint

This decision, made in 1932, ensured her work remained hidden until the 1960s and only truly gained international recognition in the 21st century. Her posthumous emergence has forced a re-evaluation of the origins of abstract art, challenging established art historical narratives that have long centered on male European artists. Af Klint's story compels us to question who writes history, whose innovations are recognized, and how personal belief systems can drive artistic creation. Her work, now celebrated, urges us to consider the often-unseen forces and forgotten individuals who shaped artistic movements, providing a vital counterpoint to conventional art historical timelines and enriching our understanding of creative innovation.

Literature, too, has its forgotten giants, whose experiences and perspectives offer insights into the human condition and the complexities of societal structures.

Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753-1784) was kidnapped from West Africa and enslaved in Boston in 1761; Wheatley learned to read and write English, Latin, and Greek. Her talent led to the publication of her first book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, in London on September 1, 1773, making her the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry. Before its publication, a group of 18 prominent Boston men, including John Hancock, had to attest to her authorship in court, a testament to the skepticism that an enslaved Black woman could produce such sophisticated verse. Wheatley's poetry frequently explored themes of freedom, Christianity, and classical antiquity, subtly critiquing the hypocrisy of a nation that professed liberty while upholding slavery. Despite her literary achievements and eventual emancipation in 1778, she struggled financially and died in poverty at the age of 31 on December 5, 1784. Wheatley's life and work illuminate the challenges faced by Black artists in early America, forcing us to confront the historical intersections of race, gender, and intellectual freedom. Her legacy is particularly relevant today as we continue to grapple with issues of racism, intellectual property, and the ongoing battle for equitable representation in literary canons. She reminds us that artistry can emerge from the most oppressive circumstances.

Zora Neale Hurston

Another literary titan whose brilliance was tragically overlooked for decades is Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960). A central figure of the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston was a novelist, folklorist, and anthropologist who meticulously documented Black American culture, particularly in the South.

Their Eyes Were Watching God, 1937

Her masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God, published in 1937, explored the journey of Janie Crawford, a Black woman seeking independence and self-discovery. Hurston's unique voice, rich in Black vernacular and folklore, set her apart but also contributed to her later marginalization. Critics, including some within the Black literary establishment, found her work too focused on the rural South and not sufficiently aligned with the protest literature popular during the Civil Rights era. By the 1950s, Hurston had faded into obscurity, working as a maid and dying in poverty on January 28, 1960. It was not until the 1970s, through the efforts of author Alice Walker, that Hurston's work experienced a resurgence, finally receiving the critical acclaim it deserved. Hurston's story underscores the cyclical nature of cultural appreciation and the importance of preserving diverse narratives. Her commitment to celebrating Black Southern culture and her exploration of female autonomy align with contemporary movements advocating for cultural preservation. Her re-emergence teaches us that true cultural wealth lies in recognizing all its varied expressions, especially those that have been historically undervalued.

Mary Anning

Beyond art and literature, science and philosophy also contain brilliant minds whose contributions were dismissed or forgotten. Mary Anning (1799-1847), a self-taught paleontologist and fossil collector from Lyme Regis, England, made groundbreaking discoveries that altered scientific understanding of prehistoric life. She unearthed the first complete Ichthyosaur skeleton in 1811, a discovery that captivated the scientific community. In 1823, she found the first complete Plesiosaur skeleton, and in 1828, she discovered the first British Pterodactylus. Despite her skill in finding, excavating, and identifying fossils, her gender and working-class background meant she was largely excluded from the formal scientific societies of her time. Prominent male geologists often purchased her specimens, published papers based on her findings, and received credit, while Anning herself received little formal recognition or financial reward. She struggled with poverty throughout her life and was often denied entry to scientific lectures she had made possible through her discoveries. Her story highlights the barriers faced by women in science throughout history and the usually unacknowledged contributions of individuals outside the academic elite. Her life demonstrates how scientific advancement can emerge from unexpected places, challenging the traditional gatekeepers of knowledge.

Ibn al-Haytham

Looking further back in time, the polymath Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965-c. 1040), often known in the West as Alhazen, revolutionized the field of optics and laid the groundwork for the modern scientific method. Born in Basra (present-day Iraq) during the Islamic Golden Age, al-Haytham conducted rigorous experiments and challenged prevailing theories, including the ancient Greek belief that vision occurred when rays emanated from the eye. His seminal work, Book of Optics, completed between 1011 and 1021, correctly explained that vision occurs when light rays enter the eye from an external source. He also pioneered the use of controlled experiments, peer review, and the systematic observation and measurement of phenomena, principles that are cornerstones of modern scientific inquiry. Despite his influence on later European thinkers, such as Roger Bacon, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton, his contributions were often unacknowledged or misattributed in Western historical accounts —a typical pattern in Eurocentric narratives of scientific progress. Al-Haytham's work on optics forms the basis for technologies from eyeglasses to cameras, and his emphasis on empirical evidence and critical thinking remains relevant in an age grappling with misinformation and the importance of scientific literacy. His story pushes us to broaden our understanding of intellectual heritage, recognizing the global and interconnected nature of scientific discovery.

Reclaiming these voices is not merely an academic exercise; it is a contemporary act of relevance. By seeking out and amplifying the voices of artists, writers, and thinkers who have been historically overlooked, we gain a richer, more nuanced understanding of the past. This historical context provides the necessary context to observe human behavior, societal structures, and intellectual development. It helps us examine the biases inherent in historical narratives and appreciate the diverse wellsprings of human creativity and ingenuity. The struggles and triumphs of Artemisia Gentileschi, Hilma af Klint, Phillis Wheatley, Zora Neale Hurston, Mary Anning, and Ibn al-Haytham offer not just historical lessons but insights into the nature of power, identity, innovation, and resilience. Their stories challenge us to question whose voices we prioritize, whose histories we celebrate, and whose perspectives we allow to shape our understanding of the world. In doing so, we ground today's events in a more truthful historical continuum. This commitment to historical depth and interdisciplinary analysis promotes an informed and meaningful engagement with the complexities of the world we inhabit today.

Darrell Lee is the founder and editor of The Long Views, he has written two science fiction novels exploring themes of technological influence, science and religion, historical patterns, and the future of society. His essays draw on these long-standing interests and apply a similar analytical lens to politics, literature, artistic, societal, and historical events. He splits his time between rural east Texas and Florida’s west coast, where he spends his days performing variable star photometry, dabbling in astrophotography, thinking, napping, scuba diving, fishing, and writing, not necessarily in that order.