The Light of Alexandria

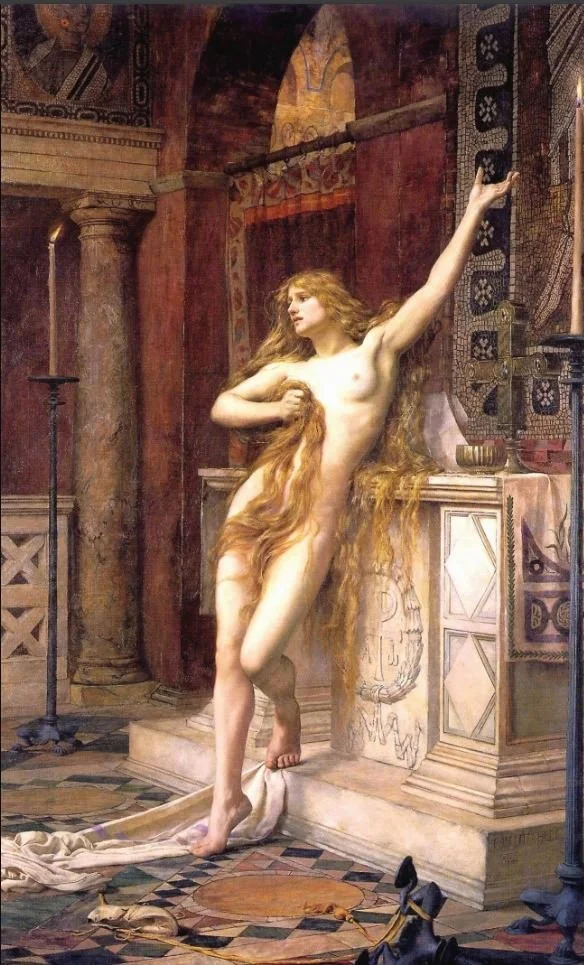

"Hypatia" by Charles William Mitchell (1885)

By Darrell Lee

In the fading light of the classical world, the city of Alexandria stood as a final, brilliant beacon of intellectual inquiry. Its legendary library and museum, though diminished from their peak, still drew scholars from across the Roman Empire. Within this vibrant hub of learning, one figure shone with a unique and powerful incandescence: Hypatia. A philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, and revered teacher, she commanded the respect of pagans and Christians alike, her classroom a rare space of civil discourse in a city increasingly torn apart by political and religious strife. Yet, it was this very influence, and her unwavering commitment to reason, that would make her a target. Her brutal murder in March of 415 CE at the hands of a frenzied Christian mob was not merely a tragic crime; it was a symbolic act, a violent tearing of the page that marked a devastating turning point in the relationship between faith, power, and science. Hypatia's life and death serve as a timeless and chilling cautionary tale, a story whose echoes can be heard in the anti-science rhetoric and politically motivated attacks on knowledge that plague our own era.

Born around 355 CE, Hypatia was the daughter of Theon, a respected mathematician and the last known head of the Museum of Alexandria. He raised her in the world of Greek intellectual tradition, providing an education that was extraordinary for any woman of her time. Hypatia quickly surpassed her peers, establishing herself as the leading mind in two of the most demanding fields of thought: mathematics and Neoplatonist philosophy. Although none of her original works survive, we are aware of her contributions through the writings of her students and contemporaries. She was not a discoverer of new theorems in the modern sense, but a masterful synthesizer, editor, and teacher who clarified and preserved the outstanding intellectual achievements of the past.

Her work in mathematics was influential, but it was just one facet of her intellectual prowess. She wrote extensive commentaries on Diophantus's Arithmetica, a foundational text in number theory, and on the notoriously difficult Conics by Apollonius of Perga, which explored the geometry of conic sections (ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas). Her edits and explanations made these dense, complex works accessible to a new generation of scholars. In astronomy, she assisted her father in revising Ptolemy's Almagest, the definitive astronomical text for over a millennium. She was credited with creating her own updated astronomical tables that charted the movements of celestial bodies. Her genius was not confined to the theoretical; she was also a gifted engineer. Hypatia is credited with designing a type of astrolabe, a complex analog computer used to solve problems relating to the position of the sun and stars, and a hydrometer, an instrument for measuring the density of liquids. These practical inventions demonstrate a mind that was not just content to contemplate the cosmos, but was driven to understand and measure it.

Beyond her scientific achievements, Hypatia was the head of the Neoplatonist school in Alexandria. Her philosophy emphasized reason and logic as the path to understanding the ultimate reality. Her classroom was a place of remarkable intellectual and religious tolerance. She taught a diverse and influential group of students, including many wealthy Christians destined for high office in the church and the state. One of her most devoted pupils was Synesius of Cyrene, who would later become a Christian bishop and whose surviving letters speak of Hypatia with reverence and profound intellectual debt. He addressed her as "mother, sister, teacher, and withal benefactress," a testament to her personal charisma and the deep impact of her mentorship. She was a public intellectual in the truest sense, a woman who moved freely through the male-dominated spheres of power and academia, her counsel sought by the city's leaders.

This very prominence, however, placed her at the epicenter of a dangerous and escalating power struggle. Fifth-century Alexandria was a cauldron of religious and political conflict. The once-dominant pagan traditions were in decline, and an increasingly militant and well-organized Christian church was asserting its authority. The two most powerful men in the city were Orestes, the secular Roman governor, and Cyril, the ambitious and uncompromising Christian Bishop. The two were locked in a bitter feud, vying for control of the city. Orestes, a Christian himself, represented the old Roman order of civil governance, while Cyril commanded the loyalty of a formidable army of monks and lay followers known as the Parabalani. Their conflict, fueled by religious fervor and political ambition, would ultimately claim the life of Hypatia.

Hypatia was a close friend and trusted advisor to Orestes. She was also a pagan, though not a religious activist. Her allegiance was to philosophy and reason, not to any particular group of particularly respected, famous, or important people. But in the charged atmosphere of Alexandria, her paganism and her influence over the governor made her a target. Rumors, fanned by Cyril's supporters, began to spread. She was branded a sorceress, a witch who was using her dark arts to bewitch Orestes and prevent him from reconciling with the Bishop. She became the scapegoat for the city's political deadlock, a symbol of the pagan intellectualism that the most zealous Christians saw as a threat to their ascendancy.

The end came with shocking brutality. In March 415, as Hypatia was traveling through the city in her chariot, she was ambushed by a mob of Parabalani. They dragged her from her carriage, hauled her into a nearby church, and there, in a sacred space, they stripped her and murdered her, scraping the flesh from her bones with sharpened oyster shells and roofing tiles before burning her remains. The act was one of savage, symbolic annihilation. It was a message, delivered in the most gruesome terms possible, that there was no room for an influential, independent, female intellectual in the new order they sought to impose. Her death sent a shockwave through the intellectual world, a clear signal that the age of classical inquiry was coming to a bloody and violent end.

The image for this essay is one of the most famous and influential depictions of her death. "Hypatia" by Charles William Mitchell, painted in 1885. This painting captures the final moments of Hypatia's life. Mitchell portrays her as a symbol of classical beauty and vulnerability, standing naked and defiant before the altar of a church as the mob closes in. Her posture, with her arms crossed and hair unbound, conveys a sense of both fear and intellectual dignity in the face of barbaric violence. The painting became an iconic image for those who saw Hypatia as a martyr for philosophy and reason, and it powerfully visualizes the moments leading up to her death.

It is tempting to view Hypatia's murder as a tragic relic of a distant, unenlightened past. Yet, the forces that led to her death—the fusion of political ambition, religious fanaticism, and a deep-seated hostility to science and reason—are frighteningly familiar. In the current political climate of the United States, we are witnessing a resurgence of anti-intellectual and anti-science rhetoric that echoes the dark currents of 5th-century Alexandria. Scientific consensus on issues from climate change to vaccine efficacy is openly attacked and dismissed by political leaders, not based on competing evidence, but because it is politically inconvenient. Scientists themselves are no longer seen as neutral arbiters of fact, but are often cast as partisan actors, their motives questioned and their findings distorted to fit a political narrative.

The persistent teachings of Young Earth Creationism illustrate this conflict between empirical evidence and dogmatic belief. Adherents to this view, based on a literalist interpretation of the Bible, insist that the Earth is approximately 6,000 years old. This belief stands in direct opposition to a mountain of evidence from virtually every field of science. Radiometric dating of rocks, the study of the cosmic microwave background, the geologic record, and the fossil evidence for evolution all independently and overwhelmingly point to an Earth that is 4.5 billion years old and a universe that is nearly 14 billion years old. Yet, for the true believer, this scientific consensus is dismissed as a conspiracy or a delusion. This is not merely a fringe belief; it influences public policy, most notably in the decades-long political battles over the teaching of evolution in public school science classrooms. The attempt to replace scientific theory with religious doctrine is a modern manifestation of the same impulse that drove the mob in Alexandria: a desire to make the world conform to a pre-existing belief system, even if it means rejecting observable reality.

This hostility is not limited to rhetoric; it has been translated into official policy. The current Trump administration, for example, has consistently sought to sideline scientific input and defund critical research, particularly in the realm of climate change. His administration has proposed significant budget cuts for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), agencies on the front lines of climate research. By appointing officials who openly question the scientific consensus on global warming and by systematically rolling back environmental regulations grounded in decades of research, the administration wages a different kind of war on science. It is a war of attrition, aiming not to kill the scientist, but to starve their research, dismantle their institutions, and render their conclusions irrelevant to policy. This institutional dismantling of scientific authority serves the same ultimate purpose as the mob's actions in Alexandria: to remove an inconvenient source of truth that challenges a desired political outcome.

The assault on public health science has been further amplified by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has built a political identity around attacking the scientific consensus on vaccines. For years, Kennedy has promoted the long-debunked theory linking vaccines to autism, leveraging his famous name to give credibility to claims that have been overwhelmingly rejected by mainstream medical science. His rhetoric goes beyond simple skepticism; he frames the issue in conspiratorial terms, portraying public health agencies as corrupt pawns of the pharmaceutical industry. In his book, The Real Anthony Fauci, Kennedy accuses the doctor of helping to orchestrate a "historic coup d'etat against Western democracy." This language is not the language of scientific disagreement; it is the language of incitement. By casting scientists as malevolent, tyrannical figures, such rhetoric works to erode public trust in the very institutions designed to protect public health, creating a climate of suspicion and hostility that mirrors the slander campaign waged against Hypatia. The personal attacks on Dr. Anthony Fauci during the COVID-19 pandemic exemplify another modern-day manifestation of this dangerous trend. A career public servant and one of the world's leading experts on infectious diseases, Dr. Fauci became the subject of a relentless campaign of vilification. He was not just disagreed with; he was demonized. He was accused of orchestrating the pandemic, of lying to the public. He was subjected to credible death threats that necessitated a full-time security detail for him and his family. This was not a genuine scientific debate; it was a political targeting of a scientist whose evidence-based guidance was perceived as an obstacle to a particular political agenda.

While a direct modern parallel of a scientist being murdered by a religious mob in the United States has not happened, the underlying sentiment of hostility has. The story of Hypatia is not just about the final, violent act; it is about the culture of slander and hatred that made it possible. When political and ideological leaders encourage their followers to view scientists and intellectuals as a malevolent "other," as an elite group conspiring against the ordinary person, they create a fertile ground for hostility and, in the extreme, violence.

Hypatia's legacy, therefore, is not just that of a brilliant mind extinguished too soon; it is that of a martyr for reason. Her murder serves as a powerful historical lesson on the catastrophic consequences of allowing ideology to silence inquiry. She was killed not because her science was wrong, but because it was influential, and because her intellectual authority challenged the absolute power that men sought to wield. Her story reminds us that scientific literacy and critical thinking are not just academic pursuits; they are essential safeguards for a free and functioning society. A culture that respects evidence, that values civil discourse, and that protects its scientists and intellectuals from politically motivated attacks is a culture that can solve its problems and progress. A culture that, like the mob in Alexandria, chooses to scrape away the flesh of reason with the sharp edges of fanaticism is a culture that is marching into a self-imposed darkness. The light of Hypatia was put out sixteen centuries ago, but the fight to keep truth and reason alive remains as urgent as ever.

Darrell Lee is the founder and editor of The Long Views, he has written two science fiction novels exploring themes of technological influence, science and religion, historical patterns, and the future of society. His essays draw on these long-standing interests and apply a similar analytical lens to politics, literature, artistic, societal, and historical events. He splits his time between rural east Texas and Florida’s west coast, where he spends his days performing variable star photometry, dabbling in astrophotography, thinking, napping, scuba diving, fishing, and writing, not necessarily in that order.