Art as Resistance from Goya to Ai Weiwei

By Darrell Lee

In the face of overwhelming state power, systematic repression, and the crushing weight of authoritarian control, what recourse remains for the human spirit? Throughout history, alongside overt political action, armed struggle, and philosophical dissent, art has consistently emerged as a potent, persistent, and perilous form of resistance. Art is seemingly harmless, a canvas daubed with paint, words arranged on a page, sounds shaped into melody, or a fleeting performance. However, art possesses a unique capacity to challenge tyranny, subvert dominant narratives, preserve forbidden truths, and affirm human dignity against forces seeking to erase it. It operates in the realm of symbol, emotion, and shared understanding, often slipping past the censor's grasp or speaking directly to the heart in ways political tracts cannot. From Francisco Goya's harrowing depictions of the Peninsular War's brutality to Ai Weiwei's multifaceted defiance of the modern Chinese state, a lineage of artistic resistance stretches across centuries and continents. Analyzing these artists' diverse strategies, such as satire, allegory, witnessing, or direct protest, reveals the enduring power of creative expression and the complex, dangerous interaction between the artist and the oppressive regimes they dare to confront. Art against power is rarely a simple equation; it is a testament to courage, a gamble with consequence, and a vital assertion of humanity in the darkest times.

Why does art, often perceived as a luxury or mere decoration, prove so threatening to authoritarian power and so effective as a tool of resistance? Its power lies in its ability to operate on multiple levels simultaneously. Art bypasses purely rational argument, tapping into deep emotional reservoirs and shared cultural symbols. It can create solidarity among the oppressed and expose the hypocrisy or brutality of the oppressor in ways that last long after political speeches fade. The strategies employed are as diverse as the art itself. The most fundamental role is that of documentation. Art can serve as a vital, visceral record when regimes seek to control history, erase inconvenient truths, or deny atrocities. It preserves memory, gives voice to the silenced, and confronts viewers with realities the state wishes to conceal. Depicting suffering or injustice becomes an act of defiance against enforced forgetting.

George Grosz, Remembering, 1937

Laughter can be a powerful weapon against pomposity and tyranny. By ridiculing dictators, exposing the absurdity of propaganda, or highlighting the corruption of officials, satire erodes the aura of fear and infallibility upon which authoritarian power often relies. Artists like Honoré Daumier, who skewered the French monarchy, and George Grosz, who eviscerated Weimar-era militarism, used caricature to deliver biting political commentary.

Direct criticism is often impossible under repressive regimes. Artists frequently turn to parables, metaphors, and symbolism to convey subversive messages indirectly. A seemingly innocent landscape might contain hidden political commentary; a historical or mythological narrative can parallel contemporary oppression; animal fables can critique human rulers. This coded language allows dissent to circulate beneath the censor's radar, requiring an engaged audience to decipher its meaning and fostering a sense of shared, secret understanding.

Some art eschews subtlety for confrontation. Posters, murals, songs, and performances explicitly call out injustice, demand change, or seek to mobilize popular action. While often facing the swiftest and harshest repression, this artistic resistance aims for immediate political impact.

Oppressive regimes rely heavily on national symbols, iconography, and official aesthetics. Resistant artists can subvert these symbols, using them ironically or repurposing them to expose the regime's hypocrisy or brutality, thereby undermining the state's attempt to monopolize cultural meaning.

Beyond individual artworks, making and sharing art outside state-controlled channels can be a form of resistance. Underground galleries, clandestine literary circles, and unofficial music scenes can foster communities of dissent, preserve cultural identity, and provide spaces for free expression, however limited. These strategies are not mutually exclusive; artists often blend them, adapting their approach based on the specific political climate, the risks involved, and their artistic medium.

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) provides an example of an artist grappling with political upheaval and using his work to bear witness to unspeakable brutality. Initially a successful court painter serving the Spanish monarchy, his career spanned a period of immense turmoil: the Enlightenment's influence, the French Revolution's aftermath, the Napoleonic invasion of Spain (1808-1814), the brutal guerrilla warfare of the Peninsular War, and the subsequent repressive restoration of the Spanish monarchy. This immersion in violence and political failure shaped his later work.

There isn’t time now

His series of etchings, The Disasters of War, created mainly between 1810 and 1820 but published posthumously, stands as a landmark of artistic resistance through witnessing. In eighty-two prints, Goya documented the horrors he observed or heard about during the Peninsular War. He depicted not heroic battles but the grim reality of conflict: summary executions, rape, mutilation, starvation, the desecration of corpses, and the suffering inflicted on civilians by both French occupiers and Spanish forces (including guerrillas and the restored monarchy's reprisals). Prints like "Great deeds! With dead men!" or "This is worse" refuse any romanticization of war, forcing the viewer to confront its absolute dehumanizing impact. Goya's captions are often harsh, ironic, or despairing ("I saw it," "One can't look"). By refusing to sanitize the violence or take a simple partisan stance, he critiques atrocities on all sides, as well as fanaticism and superstition in later plates; Goya provides a universal indictment of war's inhumanity and the failure of reason. The series was too dangerous to publish during his lifetime, highlighting the risks inherent in such truth-telling.

The Third of May 1808 (1814)

His iconic painting, The Third of May 1808 (1814), offers a more direct, though still human, depiction of political violence. It portrays the execution of Spanish civilians by Napoleon's soldiers in reprisal for an uprising. Goya masterfully uses composition and light to create an emotional impact. The faceless, machine-like firing squad contrasts with the illuminated, terrified central figure, arms outstretched in a pose reminiscent of Christ's crucifixion, symbolizing innocent martyrdom. The fear and despair on the faces of those awaiting death are rendered with harrowing realism. It is not just a historical record but a statement about tyranny, the brutality of state-sanctioned violence, and the sacrifice of ordinary people. Goya's work set a precedent, demonstrating art's capacity to transcend mere reportage and convey the emotional and moral weight of political oppression and conflict.

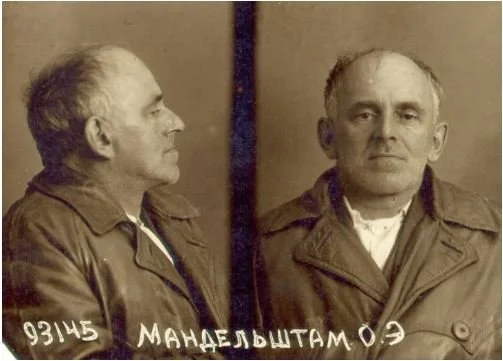

NKVD profile photo of Osip Mandelstam

The 20th century, marked by world wars, revolutions, and the rise of totalitarian regimes, saw artists repeatedly confronting state power. In the Soviet Union, the official doctrine of Socialist Realism demanded art serve the state's ideological goals, depicting idealized visions of communist life. Artists who deviated faced censorship, persecution, or worse. Yet, resistance persisted through coded literary works (like Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita), the poignant poetry of figures like Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam, who bore witness to Stalinist terror, and the unofficial, underground art movements that kept alternative visions alive through self-publishing.

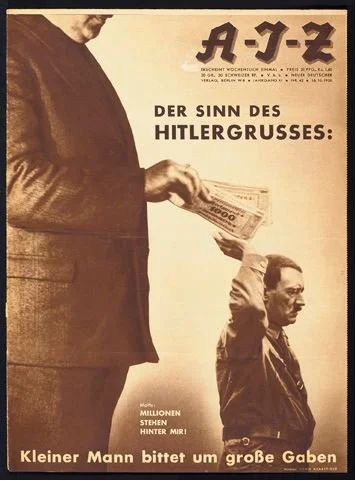

Germany, 1932

In Nazi Germany, the regime actively sought to control culture, denouncing modern art as "degenerate" and promoting a heroic, neoclassical style aligned with its racist ideology. The infamous 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition aimed to mock and discredit modernism. Many artists fled, while others engaged in forms of resistance. John Heartfield, a pioneer of photomontage, created powerful anti-Nazi images from exile, using satire and juxtaposition to expose the absurdity and brutality of the regime, such as his image of Hitler receiving Nazi salutes funded by big business. His work exemplifies direct, politically charged artistic protest.

Víctor Jara's grave in the General Cemetery of Santiago. The note reads: "Until victory..."

Across Latin America during periods of military dictatorship in the latter half of the century, art became a vital tool for dissent. The Nueva Canción movement saw musicians like Víctor Jara in Chile use folk music to voice social protest and solidarity, often at significant personal risk. Jara was tortured and killed after the 1973 coup. Muralism, particularly in Mexico but influential elsewhere, provided a public canvas for depicting revolutionary history and social struggles. Literature, too, played a crucial role, with authors employing magical realism or direct testimony to critique authoritarianism and explore its psychological impact. Following the revolution, artists navigated complex relationships with the state in Cuba. While some art aligned with revolutionary ideals, others used parables, coded language, or conceptual approaches to critique limitations on freedom or societal issues. Performance artists like Tania Bruguera have directly challenged state power through provocative works exploring censorship and political control, often facing detention and harassment. More recently, figures like Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and the associated San Isidro Movement have used performance, protest art, and online mobilization to directly confront the regime over freedom of expression, leading to significant state repression and international attention. These examples highlight the ongoing use of art for critical commentary and resistance, even within long-standing authoritarian regimes.

Globalization and digital technology have reshaped the landscape of oppression and resistance in the 21st century. The internationally renowned Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei (born 1957) exemplifies the contemporary artist navigating this complex terrain. His work confronts the power of the modern Chinese state, leveraging both traditional artistic forms and the tools of the digital age.

Ai's resistance often takes the form of bearing witness and demanding accountability, where the state seeks silence and control. Following the devastating 2008 Sichuan earthquake, the government suppressed information about the shoddily constructed schools that collapsed, killing thousands of children. Ai launched a "Citizens' Investigation," using his blog and volunteers to gather the names of the dead children, an act of remembrance and a direct challenge to state censorship. The resulting artwork, Remembering, displayed thousands of children's backpacks spelling out a quote from a grieving mother, while another piece, Straight, meticulously straightened thousands of tons of rebar recovered from the collapsed schools—a monumental, physically demanding act of memorialization.

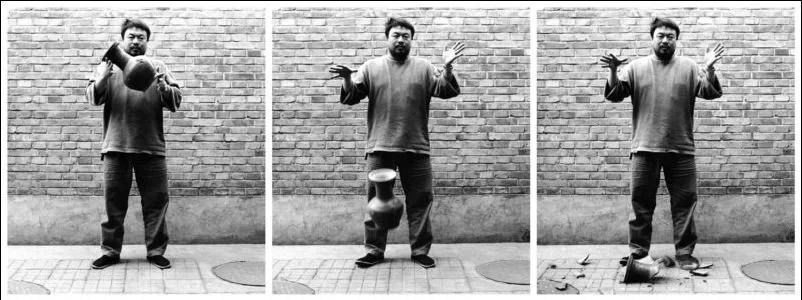

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995)

His work frequently employs powerful symbolic gestures. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), a panel of three photographs showing him shattering an ancient artifact provoked outrage. Still, it served as a potent commentary on cultural destruction (past and present), the nature of value, and dissent. His installation Sunflower Seeds (2010) at the Tate Modern, consisting of millions of individually handcrafted porcelain sunflower seeds covering the gallery floor, invited multiple interpretations: critiquing mass production and labor ("Made in China"), referencing Maoist propaganda (Mao as the sun, the people as sunflowers), while also highlighting the potential of the individual within the collective.

Crucially, Ai Weiwei masterfully utilizes the internet and social media as integral parts of his practice. His blog (before it was shut down) and active presence on platforms like X allowed him to communicate directly with a global audience, bypassing state-controlled media. He documented his harassment and detention by authorities, turning his personal experience into a form of performance art and political statement. This digital activism amplifies his message, mobilizes support, and brings international attention to human rights issues in China. His later work, including the documentary Human Flow, extends his focus to global crises like the refugee situation, continuing the theme of bearing witness to suffering often obscured by those in power.

However, Ai Weiwei's career also illustrates the risks. He has faced constant surveillance, censorship, the destruction of his Shanghai studio, physical assault, and an 81-day secret detention in 2011 on charges seen as politically motivated. His experience underscores the precarious position of the dissident artist under a powerful authoritarian state that increasingly employs sophisticated technological tools for control.

The relationship between resistant art and oppressive power is inherently fraught and dynamic. Regimes recognize art's potential influence and employ tactics to neutralize it, such as banning works, shutting down exhibitions, and controlling publishing houses and media. They sometimes promote state-sanctioned art (like Socialist Realism) that reinforces official ideology while marginalizing or persecuting independent voices. When all else fails, harassing, arresting, imprisoning, exiling, or even killing artists whose work challenges the regime or labeling critical art as foreign-influenced, decadent, subversive, or simply "bad art."

Artists, in turn, operate in this landscape with varying degrees of risk and subtlety. Some choose exile to continue their work freely. Others remain within underground networks. Some engage in direct, high-risk confrontations. The impact of their work is often difficult to measure directly. Art rarely topples regimes on its own. Its power is subtle and long-term for shaping consciousness, preserving memory, fostering critical thinking, providing solace and solidarity, inspiring hope, and keeping alternative possibilities alive. It contributes to the erosion of legitimacy or fuels the courage needed for social and political change.

The digital age adds further complexity. While technology allows dissident artists like Ai Weiwei to reach global audiences and bypass state media, it also provides regimes with powerful tools for surveillance, censorship, and targeted disinformation campaigns against artists. The international spotlight can offer protection but can lead to accusations of being a foreign agent or tool.

From Goya's dark etchings capturing the unvarnished horrors of war and occupation to Ai Weiwei's conceptually driven, digitally amplified activism challenging a modern surveillance state, art has consistently served as a vital form of resistance against oppression. Employing strategies ranging from subtle symbolism and biting satire to resolute documentation and direct protest, artists have dared to speak truth to power, challenge manufactured realities, and assert the enduring value of human dignity, creativity, and freedom.

This role is neither safe nor simple. Artists who resist face censorship, imprisonment, exile, and violence. Regimes actively seek to control, co-opt, or crush artistic expression that deviates from their narrative. The direct political impact of art can be ambiguous and hard to quantify. Yet, its enduring significance lies in its unique ability to touch the human spirit, preserve memory against enforced amnesia, foster empathy, question authority, and imagine alternatives. In societies where political dissent is stifled and open debate is impossible, art often becomes one of the last means where truth can find refuge and the hope of resistance can be kept alive. The works of Goya, Ai Weiwei, and countless others stand as powerful reminders that even under the most oppressive conditions, the creative impulse to question, witness, and resist cannot be entirely extinguished by authoritarian regimes. The unsilenced brush, defiant word, and resonant musical note remain essential tools in the ongoing struggle for human freedom and dignity.

Darrell Lee is the founder and editor of The Long Views, he has written two science fiction novels exploring themes of technological influence, science and religion, historical patterns, and the future of society. His essays draw on these long-standing interests and apply a similar analytical lens to politics, literature, artistic, societal, and historical events. He splits his time between rural east Texas and Florida’s west coast, where he spends his days performing variable star photometry, dabbling in astrophotography, thinking, napping, fishing, and writing, not necessarily in that order.